An adult fish trap, termed a resistance board weir, was installed in the Elwha River in September 2010 to begin counting adult salmon, trout, and char migrating upstream and downstream in the Elwha River. The weir is part of a multi-agency effort, which includes the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Olympic National Park, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Geological Survey, and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW), to monitor the influence of removing two Elwha River hydroelectric dams on salmon and steelhead returns to the Elwha River ecosystem. The goal of the project is to count migrating adult salmon and steelhead to determine if run sizes increase in the Elwha River following dam removal. A portion of the adult salmon captured at the weir will also be used as broodstock for hatchery production and conservation. Hatcheries will be used for Chinook salmon, coho salmon, chum salmon, pink salmon, and steelhead as a safeguard to protect Elwha River salmon runs during dam removal, which is expected to result in short-term sediment concentrations that may kill adult salmon. In addition, information will be obtained from the weir to determine when different species of adult salmon enter the river, their age, and genetic makeup.

|

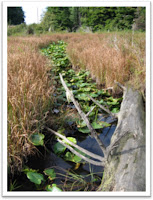

| Adult trap (resistance board weir) in the Elwha River |

At 195 feet across, the Elwha weir is thought to be the largest floating weir on the WestCcoast. The weir consists of 52 floating panels connected to a substrate rail. The substrate rail is comprised of 10-foot sections of 3-inch angle iron which are bolted together and secured to the streambed using rebar stakes. The floating panels block fish migration and direct the fish to one of four trap boxes; these boxes can be placed in different positions as needed. There are currently three upstream trap boxes---two on one side of the river and one on the opposite bank. There is also one downstream trap box. Now that the substrate rail is in place, the weir can be installed in approximately 2 days and removed in only a few hours.

The new Elwha weir fished for 30 days in 2010 and captured a total of 492 adult salmon and trout, representing eight different species, including Chinook, pink, chum, coho, and sockeye salmon, steelhead, cutthroat trout, and bull trout. Chinook salmon were captured in the greatest number---461 individuals. Pink salmon were the next most common species captured with 12 individuals. Although the weir was pulled prior to the peak of the coho and chum salmon runs, both species were captured. In addition, summer-run and/or early returning winter-run steelhead were captured. The capture of pink salmon surprised us, since pinks generally return to Puget Sound rivers only during odd years (2009, 2007, etc.). They have, however, become more common during even years over the last decade.

|

| The weir fishing at 2,200 cfs |

The weir is planned to fish a majority of the time during the summer and early fall, when Chinook and pink salmon are migrating into the Elwha River. However, it is expected to fish only part-time during late fall through spring when storms and/or snow melt result in high water in the river. The weir fished successfully during flows of 2,200 cubic feet per second (cfs) in late summer (500 cfs is the normal low flow during summer). This was encouraging, since the weir was predicted to be able to fish up to about 2,000 cfs.

The weir is planned to be re-installed in early 2011 to direct adult steelhead to the river margins where they will be counted using SONAR. The trap boxes will be installed in late winter or early spring to trap adult steelhead. The weir will be removed again during the spring snow melt and then reinstalled with traps as flows begin to decrease in early summer.

This project was funded in part by funds provided to the cooperating agencies as part of their annual budget. Additional funds were obtained through the President’s stimulus program (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act). The project is currently funded through September 30, 2012.

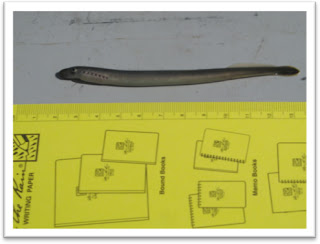

Here are some of the fish captured by the weir:

|

| Chinook salmon |

|

Coho salmon

|

|

| Chum salmon |

|

| Pink salmon |

|

| Sockeye salmon |

|

| Bull trout |

|

| Cutthroat trout |

|

| Steelhead |